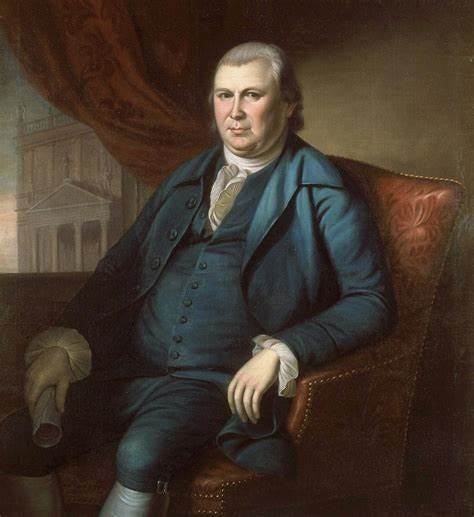

Robert Morris Jr. the Founding Father that Financed the American Revolution

When Robert Morris signed the Declaration of Independence, he was the wealthiest man in the American Colonies.

When Robert Morris signed the Declaration of Independence, he was the wealthiest man in the American Colonies. Unfortunately, within years of the signing of the United States Constitution, he had found himself in abject poverty. So how Did Robert Morris Fall from the highest level of wealth to spending years in Debtors Prison?

Robert Morris Jr. Was born to Robert Morris Sr. and Elizabeth Murphet in Liverpool, England in 1734. Elizabeth would die in 1736 and Robert Sr. would leave his two-year-old son in the care of his grandmother to seek work in the American colonies.

Robert Sr. spent the next decade building a successful career as a tobacco Merchant in Maryland. He was so successful that he became the authority when it came to the trade. He was the driving force behind the tobacco inspection law, which was adopted despite strong opposition from many colonial merchants.

At the age of 14 in 1748 Robert junior joined his father in Maryland. After a few months, Robert Jr. was sent to live with a family friend in Philadelphia and began working as a clerk at the merchant firm of Charles Willing & Co. In 1750, Robert Morris, Sr. was leaving a dinner party on one of his company's ships. A goodbye salute was fired from the vessel as he departed in a small boat. Unfortunately, the shot was ill-timed, and Robert Sr. was not far enough away. the shot burst through the side of the small boat, seriously injuring him. he died of blood poisoning because of the accident in 1750. Leaving his young 15-year-old son orphaned.

Young Robert was taken in by his employer, Charles Willing. Willing taught Morris all about business and the in and out of the Merchant trade. In 1754 Morris would open one of the Colony’s first Coffee houses in Philadelphia called the London Coffee House on Front Street. The Coffee house was partially funded by Publisher William Bradford and the Pennsylvania Gazette. You may have seen Bradford’s political cartoon in history class, protesting the Stamp act.

During the Seven years’ war, Robert was dispatched to Jamaica as a ship captain on a trading voyage. During the trip, French mercenaries captured him. Fortunately, he and his crew fled and sought refuge in Cuba. He returned to Philadelphia when an American ship landed in Havana.

Morris's former guardian, Charles Willing died during this period, and his son, Thomas Willing, inherited his father's business. Thomas offered Robert a partnering position, and the business of Willing, Morris & Co. was established. They started with three ships that were dispatched to the West Indies and England, exporting American goods, and importing British cargo. Willing and Roberts tried their hand and importing slaves but quickly found the practice abhorrent. In 1769 the partners formed the first non-importation agreement with other merchants effectively ending the slave trade in Philadelphia. Robert’s relationship with the Company continued for 40 years making him one of the wealthiest men in the American Colonies.

Willing and Morris teamed up with other merchants in response to the new tax policy changes after the Seven Year’s War. When the Stamp Act was passed in 1765, Robert organized protests in Philadelphia. He urged the tax collector to abandon his post and return the stamps. The tax collector later claimed that he believed his house would be destroyed "brick by brick" if he did not comply. Morris was also a Bay Warden and peacefully refused to accept any tea into Philadelphia’s Harbor. He was furious with what he called the “unprofessional” way Boston managed the situation and the mess it caused for the rest of the colonies.

In March 1769, Robert Morris married Mary White and had seven children.

When shots were fired at Lexington and Concord Morris' firm supplied the militia with firearms and gunpowder, while his shipping contacts informed him of English military movements. Robert became increasingly active in the patriot cause. He served with Franklin on the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, and eventually became its chairman. Later, he was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly, and then to the Second Continental Congress.

Following Richard Henry Lee's resolution for independence on June 7, 1776, Morris was nominated to the Model Treaty Committee. This treaty proposed free trade-based international relations but did not call for any political union. Benjamin Franklin took these instructions to Paris and fashioned them into the Treaty of Alliance, which enabled the victory at Yorktown in 1781.

Morris originally spoke out against Independence and hoped for peaceful reconciliation with Britain. He believed that Americans were not prepared for self-government and that anarchy would ensue. He was also concerned that the colonists were unprepared for a fight with the era's superpower. Morris abstained from voting for independence and left the room so that the vote could pass.

when it came time to sign the Declaration on August 2 he did so, recognizing the value of unanimity among the delegates. He said at this time that it was “the duty of every individual to act his part in whatever station his country may call him to in hours of difficulty, danger, and distress.” From that moment forward Morris performed services in support of the war that would earn him the moniker of “Financier of the Revolution.”

While in Congress Morris was on the Secret Committee, from which he used his commercial contacts as a network of secret agents for the cause. He was a member of the Committee of Correspondence, which would later become the U.S. Department of State. He served on the Marine Committee and was the only member of that Committee for a time. He is now on the flag committee when Congress ratified the American Flag during Marine Committee business. He sold his best ship to the Continental Navy, and it was renamed the Alfred, and sold a second one, which became the Columbus. He later sold a third which was renamed the Reprisal and this ship took Franklin to France. Many captains who sailed for Morris became naval officers in the Revolution including John Barry, Lambert Wickes, John Green, and Samuel Nicholas, who became the first Commandant of the Marine Corps. Morris supplied Washington’s army with timely financial aid, weapons, and blankets.

In 1779 Thomas Paine and Henry Laurens delivered charges of fraudulent transactions against Willing and Morris. Morris demanded that a congressional committee examine his books, and he was exonerated. The committee reported, “that (Robert Morris) …has acted with fidelity and integrity and an honorable zeal for the happiness of his country.” (DSDI, 2008)

in 1781, congress appointed Morris the Superintendent of Finance. This was the first executive office in American history. Faced with a serious governmental monetary crisis, Morris submitted the first national funding proposal, On Public Credit, which served as the basis for Hamilton’s plan submitted a decade later during the Washington Administration. Morris established the Bank of North America with the help of two other signers—James Wilson and George Clymer. Morris slashed governmental and military expenditures, personally purchased Army and Navy supplies, tightened accounting procedures, and pleaded with the states to contribute, a process he likened to “preaching to the dead.” Before he left office, he used over a million dollars in his notes to feed and pay the troops, with most of those notes to be repaid with loans from France. At the end of the war, he took on the mission of repaying the debt to France, but circumstances made that impossible and he lost a fortune in the effort.

He provided support for the Continental Army and Generals Washington and Lincoln as they marched to Yorktown. He put up 1.4 million dollars for the effort and coordinated with the French to get French ships into the Chesapeake, which made the planned evacuation of the British army impossible.

Morris signed the new U. S. Constitution, one of only two signers of the Declaration of Independence to sign all three basic founding documents—the Declaration, the Articles of Confederation, and the U.S. Constitution.

When Washington became President, he invited Morris to become his Secretary of the Treasury. Morris declined to serve, but recommended his friend, Alexander Hamilton, for the post. That same year he was elected a United States Senator, a post which he served until 1795.

Morris lent his house to Washington and, later, John Adams when the capital of the United States was temporarily relocated to Philadelphia, making his home the Executive Mansion before the White House.

In the latter years of his public career, Morris made irrational investments in Western and DC-area land, frequently using credit. To make matters worse, in 1794 he began building a home on Philadelphia's Chestnut Street designed by Maj. Pierre Charles L'Enfant is also on credit. Not long after, Morris sought to avoid creditors by fleeing to The Hills, his rural house on the outskirts of Philadelphia near the Schuylkill River.

Arrested at the demand of creditors in 1798 and forced to abandon completion of the mansion, which became known as "Morris’s Folly" in its unfinished state, Morris was sent into the Philadelphia debtor's prison, where he was treated well. However, by the time he was released in 1801, his property and wealth were gone, his health had worsened, and his spirit had been shattered. He remained in poverty and obscurity, living in a modest Philadelphia house on an annuity obtained for his wife by fellow signer Gouverneur Morris.

Robert died May 8, 1806. He is buried behind Christ Church in Philadelphia.